The 10 Best Films of 2025

2025 was exactly like every year in the history of cinema in its quality. The only variable every year is whether or not one watched the best the year had to offer.

In the conclusion of his book Directed by Yasujirō Ozu, Japanese literary and film critic Shiguéhiko Hasumi muses about overreading and overinterpreting motion pictures at the expense of actually watching them. He declares, “In cinema, the tendency to overread often corresponds to the poverty of what one has seen.” The phrase “poverty of what one has seen” returned to me a lot this year, particularly in reference to the annual claims that 2025 was either a dreadful or wondrous year for cinema from various corners of the internet. Quantity has nothing to do with this poverty either: it is a curation problem. In truth, 2025 was exactly like every year in the history of cinema in its quality. The only variable every year is whether or not one watched the best the year had to offer.

The best films I saw this year came from places as varied as Palestine and Lithuania to China and Norway, although a few notable countries like India and South Korea are missing. This is, as noted above, a reflection of my own viewing poverty. I did not watch as many new Korean and Indian films as usual, so it was harder for something good to snag a top spot. A few of them tug on the anxieties of aging (particularly into one’s 30s), and several of this year’s best, from the beloved Jia Zhangke’s Caught by the Tides to the aching dirge from Šarūnas Bartas in Laguna, could be labeled “slow cinema.”

As usual, my list uses an arbitrary criterion for defining new releases. Both 2025 theatrical or streaming releases and festival circuit exclusives were fair game as long as they were new to me and new to the year in some form or another. Some of the festival releases may not be available for theatrical viewing or streaming until 2026 or later, so they might not make sense to include alongside the former, but I find the arbitrary nature of the criterion to be most inclusive to both my tastes and viewing habits for the year.

These are the best films of 2025 that I had the pleasure of watching. The top three are masterpieces. The rest are damn good too.

Honorable Mentions: No Other Choice, Red Sonja, Mission: Impossible – The Final Reckoning, Sinners, In the Lost Lands, The Threesome, Palestine 36, Good News, Dongji Rescue, KPop Demon Hunters, Exterritorial, Hamnet

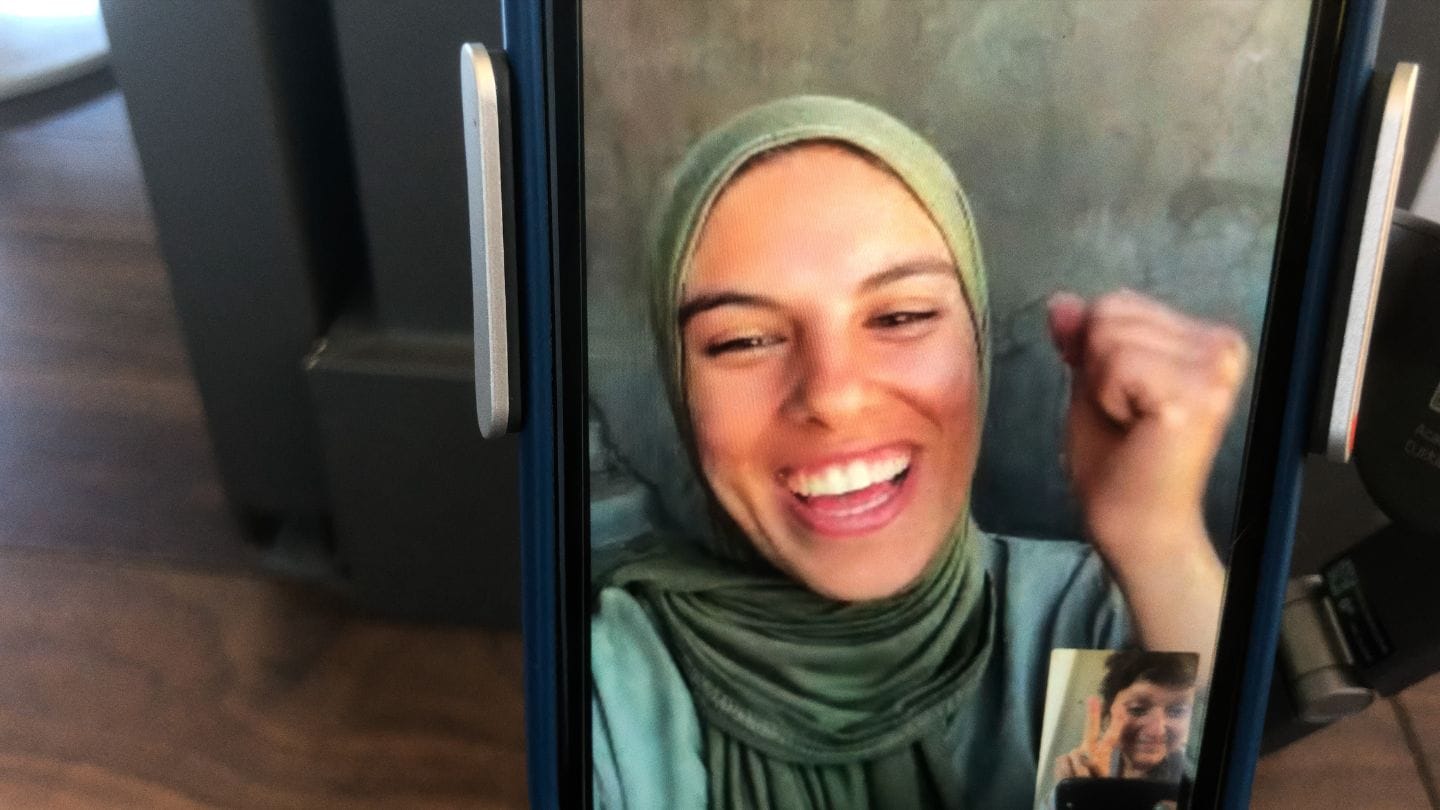

10. Put Your Soul on Your Hand and Walk (Directed by Sepideh Farsi; Palestine, France, Iran)

“Iranian director Sepideh Farsi’s Put Your Soul on Your Hand and Walk seems likely to be the most important film to screen at the 2025 Cannes Film Festival. A personal document of life under Israeli siege and bombardment in Gaza, Farsi’s film peers into what life in Gaza is like in 2025 through the eyes of a single Palestinian woman, the 25-year-old Fatma Hassona, a photographer and citizen journalist. Hassona was killed by an Israeli missile strike that specifically and precisely targeted her family’s residential apartment on April 16, 2025. Ten other members of her family, including her pregnant sister, were also killed in the strike. The state-authorized family murder happened one day after Cannes selected the film for the parallel ACID program.”

Read my full review at In Review Online and check out my interview with director Sepideh Farsi at the Boston Hassle.

9. To the Victory! (Directed by Valentyn Vasyanovych; Ukraine, Lithuania)

“‘We have nothing in common anymore,’ a wife, displaced from Ukraine to Austria, tells her husband still in Ukraine. Nothing irreconciliable hung over their marriage before the war, but the two different experiences around the conflict create new fractures. The way war completely reshapes mundane life in its aftermath is a less glorious and machismo side to armed conflict and this is why it’s less common in cinema, a medium with a preference for the ‘if it bleeds, it ledes’ mentality inherited from journalism. A Ukrainian film that blurs the lines of fiction and documentary, redraws, and then blurs them out again, Valentyn Vasyanovych’s To the Victory! aches and longs for the return of the mundane.”

Read my full review here at There Were No Gods Left and my interview with director Valentyn Vasyanovych here.

8. Eephus (Directed by Carson Lund; United States)

I never would have anticipated a baseball film would make my Best Of list. I hate baseball. But this year, my love of innovative digital cinema helped me to fall in love with Jon Bois’ The History of the Seattle Mariners, inadvertently warming me up watching the postseason antics of Shohei Ohtani and ultimately leading to me turning on Eephus as last-minute potential awards viewing.

Eephus irreverently observes from start to finish the last baseball game ever played at a soon-to-be-demolished stadium by an amateur New England baseball league. The eclectic group of men age with the night, showing the shifting anxieties and priorities we develop as we grow old. When the game goes to extra innings, the players bicker about how to play, whether or not to play, and how to still enjoy themselves while they play.

If cinema is a visual wrestling with time, then with its discursions on aging and the ticking of the hour hand, Ephesus testifies that baseball, the ultimate sport of the clock, is the king of cinematic sports.

7. Caught by the Tides (Directed by Jia Zhangke; China)

"I am unaware of a director anywhere in the world who has more thoroughly and philosophically navigated the complicated contradictions of the contemporary world than Jia Zhangke, a titan of the Chinese Sixth Generation and one of the world’s leading political filmmakers. He never approached his project to film modern life in a modernizing and technologizing 21st-century China from a place of simplistic dichotomies or myopic ideologies. His fluidity around political binaries has helped him to avoid becoming a state propagandist while never being adopted as the party’s favorite filmmaker either. His newest released film, Caught by the Tides, is the apotheosis of his life’s work and one of the most profound and emotional wrestlings with one’s own artistic catalogue ever released.

Jia’s films can never be summarized the way most narrative fictional films can be, and that’s because he also avoids narrative conventions as well as he avoids political ones. His partnership with Zhao Tao, his wife and life-long artistic collaborator, is the most consistent throughline in his filmography. Her name means 'waves' in Chinese, and Caught by the Tides more or less rides the waves of her life. We watch her age across 25 years as Jia reuses footage and outtakes from his old films (mostly Unknown Pleasures, Still Life, and Ash is Purest White), decades old footage for a project he began but never completed called Man with a Digital Camera, an obvious reference to Dziga Vertov’s Man with a Movie Camera, and original pandemic-era material. The younger Zhao loves a man named Guo Bin (Li Zhubin, also in the older films), and he runs away from Datong to Fenyang, where Zhao searches for Guo and eventually leaves him for good. They meet decades later in pandemic-China...

Zhao ages with the passing years as does China."

Read my full review at the Boston Hassle.

6. Ne Zha 2 (Directed by Jiaozi; China)

“The film event of the year belongs to China. Ne Zha 2, a Chinese animated film and sequel to 2019’s Ne Zha, isn’t just the year’s highest-grossing film at the global box office, it’s the highest-grossing animated film ever made…

The titular character is the incarnation of something called the Demon Orb. Ao Bing comes from the more noble Spirit Pearl. The demon boy and monster boy prove friendship and justice can overcome long-standing clan rivalries and their divinely ordained fates… It’s also quite serious for a children’s film, and that’s a welcome change of pace. Parents die, and a city gets the Pompeii treatment from the villain.

Ne Zha 2 is the closest thing to The Lord of the Rings since Return of the King in its sprawling magnitude and immensity. And like Lord of the Rings, director Jiaozi’s animated sequel is about vulnerable heroes who sometimes fail and need their friends to help pick them back up.”

Read my full review at The Rapidian.

5. Laguna (Directed by Šarūnas Bartas; Lithuania, Mexico)

“The most prolific filmmaker in the Baltics has returned. Šarūnas Bartas, the director behind The House and Peace to Us in Our Dreams, has been on a break since 2019. Bartas has stayed busy since 1990, even if he is known to occasionally go on streaks of four or five years without adding to his world-class filmography. This break is more understandable than most, though. In 2021, his daughter, Ina Marija Bartaitė, was tragically killed by a drunk driver while riding her bicycle. She was only in her 20s. Ina Marija followed in the footsteps of both Bartas and her mother, Russian actress Yekaterina Golubeva, and was a filmmaker herself. Bartas has two new films this year, Back to the Family and Laguna, and they both carry his reflective sensibilities forward as they philosophically meditate around family trauma and grief. Laguna documents the director and his younger daughter on a deeply personal excavation of grief and a celebration of life in the face of Ina Marija’s loss while retracing the steps of the departed in Mexico.

Ina Marija moved to Mexico’s Ventanilla Lagoon to act in a film and found solace in the Pacific Mexican coastline. Her home away from her Lithuanian home was special to her, and this memory recovery journey is the reason for Šarūnas’ (sometimes transliterated as Sharunas) latest. Some of the most tender scenes anywhere in film this year are Šarūnas and his younger daughter, Una Marija, remembering Ina Marija around small campfires in a remote Mexican forest. These discussions are simple but almost philosophical, covering topics such as life after death, grief and life celebrations, and moving on. Laguna is a heartbreaking film — for viewers going in ignorant of the context, it will be doubly so once they realize it’s a documentary — but it’s also life-giving.”

Read my full review at In Review Online.

4. Renovation (Directed by Gabrielė Urbonaitė; Lithuania)

Shot in a homey and warm 16mm, Renovation puts a beautiful Lithuanian twist on the martyred lovers genre that has become a staple of contemporary arthouse cinema (In the Mood for Love; Passages).

Ilona (Žygimantė Elena Jakštaitė) is a Lithuanian-Norwegian translator, a profession that anticipates the way she will soon come to delicately balance between two worlds. She recently moved in with her boyfriend Matas (Šarūnas Zenkevičius), and their new apartment requires some maintenance before she can call it home. One of the construction workers, a handsome Ukrainian man named Oleg (Roman Lutskyi), blamelessly captures her attention—putting her in a pickle of romances.

Director Gabrielė Urbonaitė, who previously edited the brilliant Remember to Blink, uses the sex choreography to telegraph the state of Ilona and Matas’ relationship. The first time they fuck is romantic, kinetic, and lively as they seamlessly flip-flop positions and take heed to each other’s intimate desires. Later, the sex is as lifeless as Hollywood: Ilona is distracted, and Matas grows mean.

The title gets at the crux of Renovation: change. Urbonaitė’s film is a sexy, piercing, and brutally honest film about turning 30. And, as a freshly minted 28-year-old who just moved into a (very shitty) new apartment, Renovation felt made for me.

3. Avatar: Fire and Ash (Directed by James Cameron; United States)

“‘I see you.’

This is how the characters of Pandora express love for one another. The Sully family says it more than most families. They are the sort of tight-knit family unit forged through wars, exile, and loss. They beautifully express their love through a metaphor for sight and it is not just beautiful because of the warm tenderness the verb manifests. Sight is also one of the things that makes us most human, or most creaturely. The unalive will never be able to see, to hear, or to feel. And James Cameron reminds us of this in a video introduction that plays before Avatar: Fire and Ash, where he goes out of his way to declare the film free from generative AI images. It’s straight from the hands and digital pens of artists. Real, human ones. Just as Pope Leo XIV said, AI “won’t stand in authentic wonder before the beauty of God’s creation.” Cameron makes wondrous cinema.

The third film in the Toruk Makto trilogy, Fire and Ash, testifies to our very best—and very worst—human selves. It is also the incredible capstone to one of the finest sagas in blockbuster history.”

Read my review and a feature-length essay on the film here at There Were No Gods Left.

2. The Fishing Place (Directed by Rob Tregenza; Norway)

Rob Tregenza is Kansas’ Jean-Luc Godard, and his newest film, The Fishing Place, taps into the spirit of the French maestro as he breaks the fourth wall, hunting the demons of the Nazi-sympathizing right. The American cinematographer and Cinema Parallel president has worked as the director of photography for both Béla Tarr (Werckmeister Harmonies) and Alex Cox (Three Businessmen) in between his own five features, spread across five decades — a workflow consistent with his characteristic meditative and patient photography. The first four-fifths of The Fishing Place slowly moves through the coastal Norwegian county of Telemark during Nazi occupation as Anna (Ellen Dorrit Petersen), a Nazi prisoner, is ordered by her fascist “liberator” Hansen (Frode Winther) to spy on a newly arrived Lutheran pastor, Honderich (Andreas Lust), as his housekeeper. Anna, tormented by the moral contradiction of resistance and self-preservation, finds herself desperate (and powerless) enough to collaborate. This scenic and solemn hour, which wends viewers through some of the most beautiful images of the decade, reminds us that no number of Nazis can stifle the beauty of this world.

The last 22 minutes, however, abruptly and unceremoniously cut to the extreme present with a fourth wall-breaking and fluid crane-powered long shot of Tregenza’s own film set. We hear his direction and his conversations with crew members; we watch Lust drop a cigarette; and we witness several undramatic behind-the-scenes moments. The English language enters the fray as the film jolts into the Anglo-shaped present, and the subtitles largely stop for the Norwegian. Anticipated by the question of a dying and guilt-ridden engineer whom Honderich consoles, “What do you think this place will look like in 50 years, no matter who wins?” the jolting edit simply and sufficiently translates the film’s philosophical questions around fascist collaboration and resistance to the present.

This blurb was originally written for In Review Online’s Best Films of 2025 collective list.

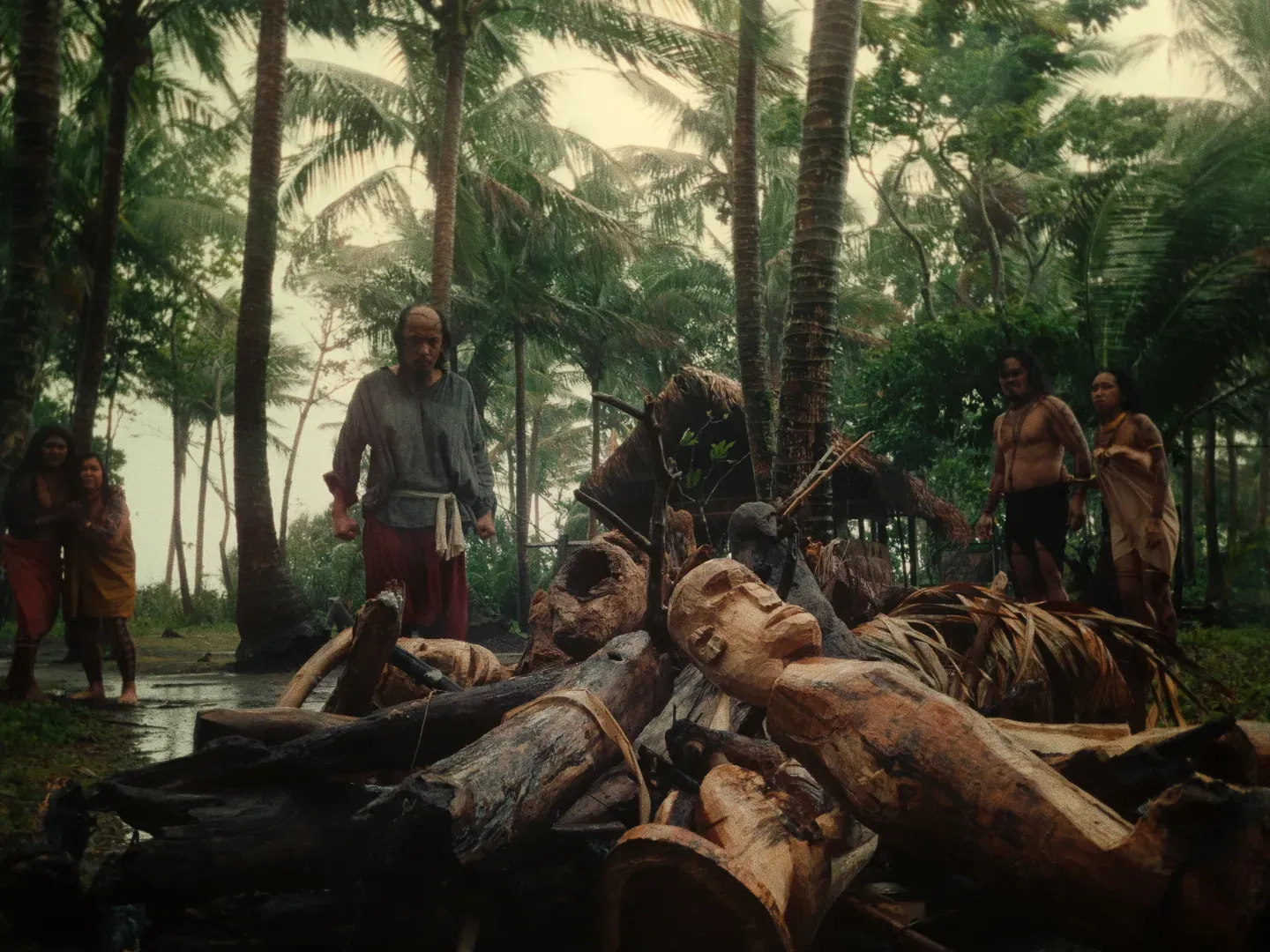

1. Magellan (Directed by Lav Diaz; Philippines, Portugal, Spain, France, Taiwan)

“‘He was a motherfucker.’ That’s what Lav Diaz said about Ferdinand Magellan in his Q&A at the 2025 Toronto International Film Festival. He also called Putin and Duterte ‘motherfuckers’ for those keeping track at home.

Diaz, the (in)famous Filipino director behind the most mammoth slow cinema films to ever actually find an audience, makes his most commercial film so far in Magellan, a selective biographical depiction of the last two decades of Ferdinand Magellan’s life. It’s shot in color and has one of the director’s shortest ever runtimes at a mere two hours and forty minutes—apparently, there is a nine-hour cut on the way though. Gael García Bernal is a professional actor worthy of international recognition and Magellan (played by Bernal) himself is also an infamous enough explorer and colonizer to cast a wider net with audiences. His name is one that most educated citizens in the West should know…

Even with the shorter runtime, Diaz maintains his signature stationary deep focus, long shots, and a minimalist score to erode the viewer’s thirst for instant gratification and dramaturgy. His emphasis on temporality makes the signature long voyage last forever, allowing viewers to come as close as ever to weathering the unrelenting durations of pre-modern sea voyages. The nine-hour cut may end up being the most painful cinematic boat ride ever if it’s any longer. The people suffering the voyage are the Portuguese and this isn’t an anomaly in Magellan. Diaz avoids reducing the titular character, the other Portuguese nobles and explorers, and the important church figures into caricatures that you might find on the Instagram brand of “post-colonialism.” One of the best scenes in the film is a teary-eyed Magellan gifting an icon of a brown baby Christ to a mother whose child is dying. In the moment, his desire to do good for this family and to help them is earnest.

Read my full review here at There Were No Gods Left.