Sholay

Experiences like Sholay are why we go to the movies.

In celebration of the 50th anniversary of Hindi cinema’s Star Wars, the Film Heritage Foundation and Sippy Films presented the newly restored Sholay at the 2025 Toronto International Film Festival. Restored to 4k, its original 70mm aspect ratio of 2.2:1 aspect ratio, the original (and more violent) ending, and with two deleted scenes, the 2025 cut of Sholay is a gift to cinema.

There isn’t a film in India with a larger legacy than director Ramesh Sippy’s Sholay, the archetypal masala film. It’s a blistering action movie, a tragic romance, an energetic and catchy musical, a breakleg comedy, and a renegade western all at once. I’m probably even leaving out a genre or two. It blends all of its ingredients so perfectly that it became the recipe for coming generations of Bollywood. Supporters of the Indian national cricket team adopted the friendship theme song, “Yeh Dosti” (This Friendship), as an unofficial anthem and Prime Minister Narendra Modi weaponized references from the film in a critique of India’s congress. Just like Star Wars, which would come out only a few years after, it’s difficult to overstate Sholay’s influence on Southeast Asian cinema.

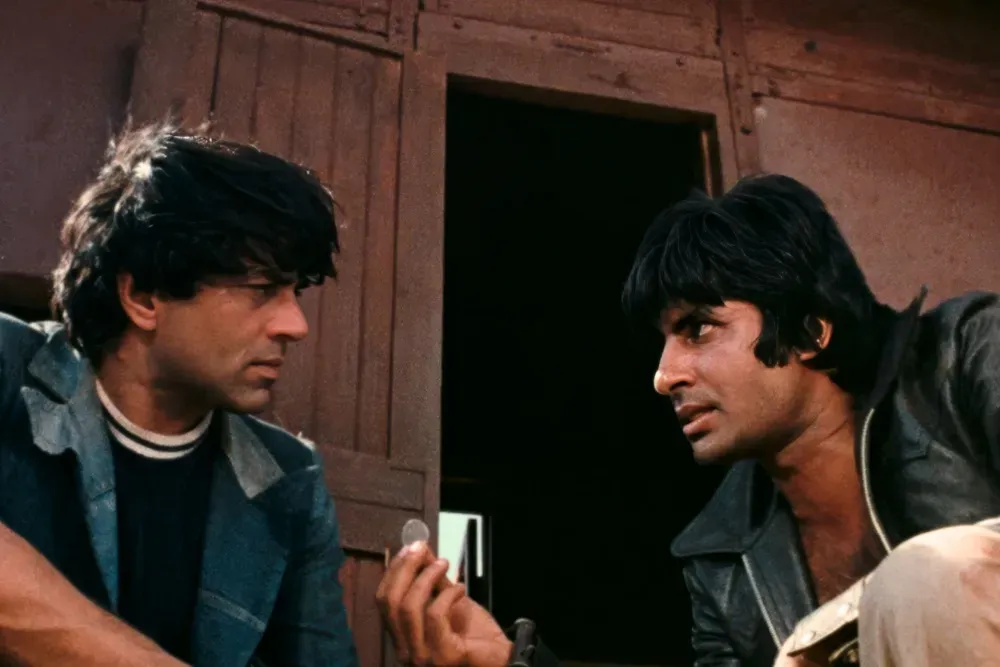

Sholay’s skeleton best resembles a cross of Seven Samurai and Once Upon A Time In The West with a little Charlie Chaplain thrown in for good measure, but it would be unfair to speak of it only in terms of non-Indian predecessors. Its legacy lies more in its near-flawless execution than sheer originality. Best friends Veeru (Dharmendra) and Jai (Amitabh Bachchan) live life as outlaw jailbirds. They aren’t all bad though. Recently retired police investigator Thakur Baldev Singh (Sanjeev Kumar), always uniformed by a concealing shawl that hides his pain and makes him look wiser, sees virtue somewhere underneath their lawlessness. He hires them to protect his small village in Ramgarh from Gabbar Singh (Amjad Khan), a notorious and bloodthirsty dacoit (or bandit) terrorizing locals.

The most violent scene—a wrenching slaughter of an entire family—should startle any sensible viewer. Sippy’s poetic direction doesn’t numbly sedate the viewer with aestheticized violence; the actual murderous acts invest more into the destabilizing effect of the violence than its gory spectacle. Cinematographer Dwarka Divecha accompanies each kill with a freeze frame that immortalizes the innocence of the victims and keeps their dignity whole. The stylish effect also arrests their lives with a violent immediacy that no acting, no fake blood could ever replicate.

The youngest member of the family is saved as the last victim. The child comes out of the house, perhaps emerging from a nap to the noise of the bloodshed, to be presented like an unwanton deer walking up to an armed woodsman as Gabbar Singh’s final victim. The deplorable man slowly trots up to the child on his horse in a scene that’s slowness Sippy painfully inflicts on the audience. With each passing second Gabbar Singh absorbs in his approach, the malice metastasizes more.

The heroes of Sholay are the best of us. One of the most iconic scenes is when Basanti (Hema Malini), Veeru’s love interest, must dance to save his life. If she stops, Gabbar Singh will order his execution. Annoyed by her impressive endurance, Singh and his men crack glass bottles all over the floor to slow her down in pain. Basanti doesn’t stop as the glass rips open her feet with every step and stride. Her love for her future husband is strong enough to endure the physical suffering.

This isn’t Basanti’s only scene of incredible love. The other is when she comforts the village’s blind and mourning imam (A. K. Hangal) and escorts him to the mosque for prayer. Sholay came out in 1975, only a few years after the Gujarat communal riots, the deadliest incident of Hindu-Muslim violence since the partition, and Ramesh Sippy was brave enough to valorize a Hindu woman escorting a Muslim man in need to a mosque! This is a long shot away from the Hindutva propaganda of modern Bollywood.

I saw Sholay for the first time with a packed audience of (mostly) Indian-Canadians at TIFF. I had never seen the less violent ending before; I didn’t know the lines of dialogue the woman to my right recited in perfect timing with the characters. For the first time in my theatre going experience, I heard an entire audience sniffle at the same time. The same woman on my left bumped my arm when wiping her tears. I cried not from the scene itself (though, I probably wasn’t far) but because of the communal experience I was witness to. A pin could have dropped and the whole audience would have heard it during the film’s saddest moments. The film’s brilliant sound design—always knowing when silence is more powerful than music—is an indelible part of this equation.

This is what Nicole Kidman is talking about in those AMC commercials. Experiences like Sholay are why we go to the movies. They are why I write about them. They are why I love them.