Shapeshifters, Religion, and Other Ghouls with Constantin Werner: Writer and Producer of In the Lost Lands

Werner gives his insights about co-writing with Paul WS Anderson, the challenges of producing the project, the differences between his screenplay and both Martin’s original text and the final film, the role of religion in the story, the filmmaking lessons he gleaned, and much more.

The civilized world ended some time ago and one feeble and draconian city remains, the accurately named City Under the Mountain. The rest is the Lost Lands, overrun by all sorts of ghouls and goons. This is the world of In the Lost Lands, the newest film from the endlessly talented director Paul WS Anderson. Milla Jovovich, Anderson’s wife and most inseparable creative partner, plays the infamous witch Gray Alys and is actively hunted by “the church,” a cultic group led by a woman known as Ash the Enforcer (Arly Jover) and decked out in medieval Templar fashion. Like a genie that can’t say no, she grants the desires of any who ask of her. The Queen (Amara Okereke) asks for the powers of a shapeshifter and Gray Alys sets off to the Lost Lands with Boyce (Dave Bautista) to find a shapeshifter and siphon its power.

Following the conclusion of the film’s theatrical run in the United States, I had the pleasure and opportunity to chat with Constantin Werner, the writer and producer of In the Lost Lands. The writing impressed me with its efficiency and patience. It takes a good screenplay to pull off that ironic balance, a screenplay that, in this case, began with Werner and was facilitated for the screen by Anderson.

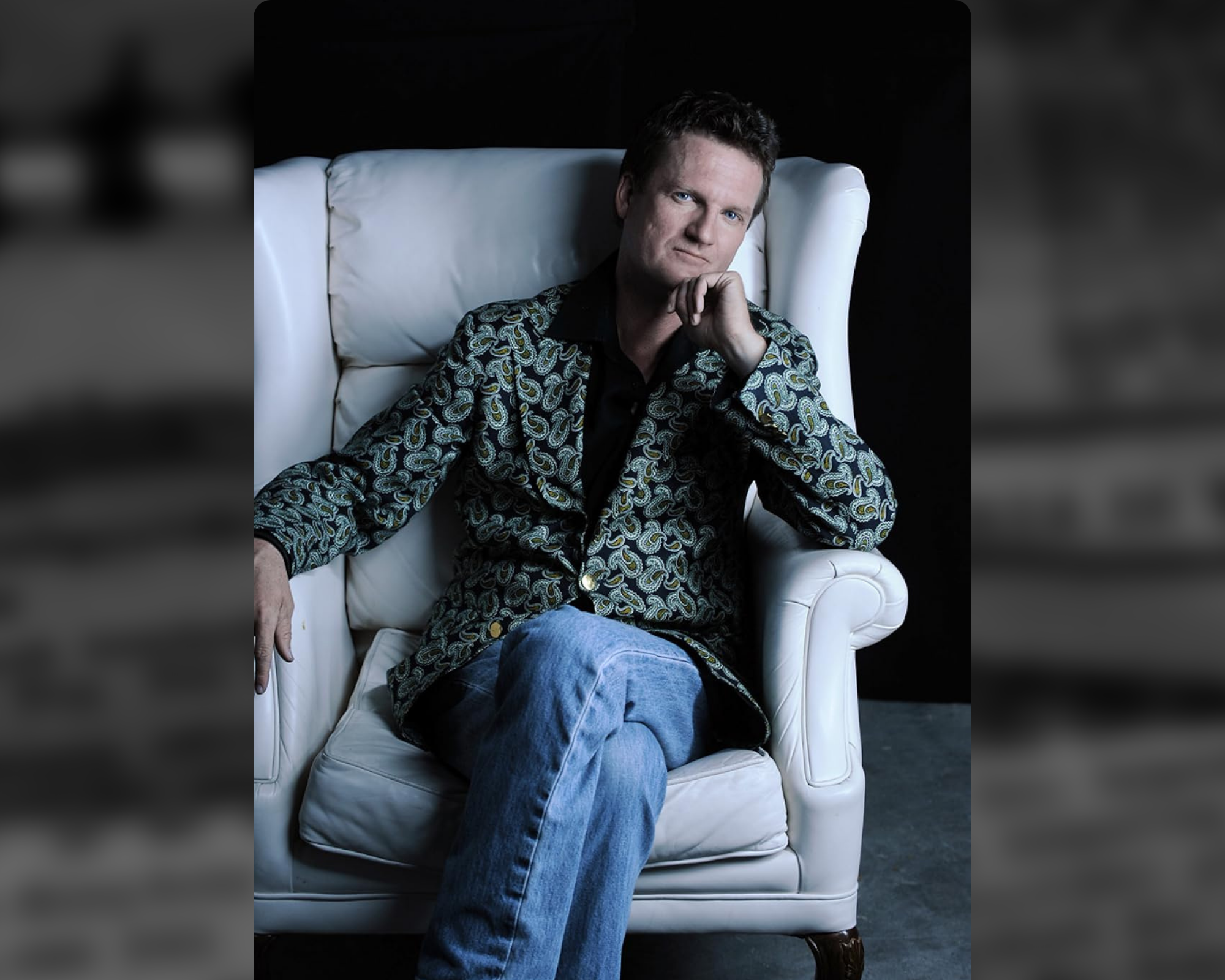

Originally from Germany, he now calls Los Angeles home. Werner works in a variety of media — novels, painting, theatre, graphic novels and comic books, music videos, film — but he is a storyteller at heart. In our time together, he told many stories, some of which I regretfully had to cut or condense for editorial purposes. He toiled away for more than a decade with the script he first optioned for Martin, nearly setting down the whole project before it even began.

Werner gives his insights about co-writing with Anderson, the challenges of producing the project, the differences between his screenplay and both Martin’s original text and the final film, the role of religion in the story, the filmmaking lessons he gleaned working with Anderson, and much more.

And, for those keeping score, he also vindicates my claim from years ago that “Paul W.S. Anderson is a religious filmmaker” by revealing what comes from what came from Martin, what came from him, and what comes from Anderson.

The interview has been condensed and edited for clarity. Read my full review of In the Lost Lands here.

Joshua Polanski: I wanted to start with the process of adapting George R.R. Martin's work and your philosophy of adaptation. How would you characterize your philosophy of adaptation? Was there a point where you felt that you had the most significant departure from Martin's original work?

Constantin Werner: The property is three stories. I optioned all three. Years ago, [before HBO aired Game of Thrones,] I made a film in the Czech Republic called The Pagan Queen, and a friend of mine recommended that I read George R.R. Martin in preparation [for Pagan Queen] because my material is very similar to the [Song of Ice and Fire] material. I was lucky to option three of George’s stories, which I originally wanted to combine into an anthology.

My first approach to the adaptation was to not change anything and have [the three] stories in a shared universe. That was the idea. After years of development and Milla Jovovich becoming attached to the project to play the lead in one of the stories, In the Lost Lands, I hit roadblocks and approached Paul [W.S. Anderson] through his wife [to see if he] would like to come on board as a producer.

He read the script, said, “This is amazing material, I love it.” We are both huge Game of Thrones fans, anthologies are great too, but it didn’t work in this case. He suggested that we extend each story and make three separate films. The [story] with Mila was obviously the first one. I stepped away from being [the director…] because if he [was] doing it, it's going to be big and he has to direct. My original film wasn’t low budget … about 10 million — but Paul works on a completely different level. I liked him a lot. We got along great. I decided to do it.

I did a page one rewrite. The way this worked was that he gave me bullet points of certain elements that he wanted in the film. For example, it originally was set in a Game of Thrones [type] fantasy medieval world. He wanted to [change] the entire backstory to dystopian. That was a huge departure.

The second [departure] was that he rightfully noted that we had a 20-page short story and it doesn't have any villains. We had to create a whole side plot with an evil empire of sorts, so that they are under pressure. In the [short], they just travel through the lost lands. They're not being pursued by anybody. The entire church and the overlord, these monks, none of that is in the original.

JP: “The witch who will not hang.” That's not in the original?

CW: Nope, nope, none of that. That's the biggest departure. Another aspect is Gray Alys, the character of Milla. She is the protagonist in a lot of Paul's films, and is known to our fans for fighting. She added that to the original character who was just doing magic.

Paul [also] really wanted to make a western. One of his idols is Clint Eastwood. Sierra [and] Once Upon a Time in the West obviously play a big [influence] here. I then integrated into the script dystopian and western [elements]. This included tricky things. For example, having a train. Paul said he wanted to have a “death train.”

JP: A death train?

CW: Because he loves these armored trains from World War I. You had these trains in World War I with cannons on top. They look completely insane. The weaponry of WWI was not as advanced as it would be in World War II, so people had funny armors, were fighting trains on horses … there was all this crazy stuff going on in military history. He really wanted that train.

In the very beginning, I was thinking, “Okay, how is a train going to pursue people who own horses? How is that going to work?” The train is just running in a straight line. It made sense to me when I saw the final film because the train line is running through a complete hell of a destroyed world. Dystopian for Paul is like 180% dystopian. It's not a little bit dystopian.

JP: One of these departures leads into my next question. There’s a lot of religion and church stuff going on In the Lost Lands. This has been prevalent in Anderson’s work throughout his career. It's also been central in a lot of your work from The Pagan Queen to some of your paintings like the “Goddess of the Rainforest.” Where does this impulse come from? And, if you're comfortable sharing, can you speak about your relationship to religion and why you return to it in your art?

CW: I also directed music videos. And generally, I consider myself close to the Gothic New Wave, the late 1980s-1990s post-punk kind of world. There's a darkly religious aspect in that type of music. That's where this comes from, in my opinion.

In Dead Leaves, I used a lot of music by Nick Cave and by Leonard Cohen, for example. It got picked up by a distributor called Cult Epics, and the owner, Nico Bruinsma (known as a director as Nico B), was a very close friend of Ross Williams in Christian Death, the new LA legendary goth death metal band who started this whole movement in the US. Using crosses and religious imagery to me is more connected to the Sisters of Mercy and Bauhaus [the band, not the architecture school] and The Cure than a criticism of religion.

I would consider myself generally spiritual. Because I like metal and goth, and this kind of stuff, paganism is not very far. The Pagan Queen had a Wiccan aspect. The female characters are witches and healers and seers. I love that in fantasy. I love The Mists of Avalon. That is one of my favorite fantasy books. I absolutely love the whole King Author legend too, The Lord of the Rings, and all of these things that are, I think, more anti-Christian. That's probably why the church is portrayed as evil. Witchcraft is good. Gray Alys is the witch and we really needed an opponent [for her.] And what is more against witchcraft than the church?

I'm a neo-pagan. I'm not practicing that because that would be too ridiculous and silly, but I do believe in certain mystical and spiritual elements from pagan times that, on one hand, I find more appealing. I also absolutely love animals and relate to the totem type of religious basic concepts. These are definitely in my paintings.

Paul's religious aspect to me is, I don’t know, to be perfectly honest.

JP: That’s okay. You don't have to speak for him. I've written a two-part essay on religion in his films, so this topic is just at the forefront of my mind. I was extra interested when you made that comment about how this was an added element that wasn’t in the original screenplay and it wasn't in Martin’s text. I wanted to interrogate that a little bit more.

I also find it interesting that you said the way religion's used is villainous. At the same time, the church, it's almost just a power costume more or less. There are no deep-seated beliefs that we would recognize as the Christian Church of our world other than the symbol of the cross and some small things like that.

CW: That’s true.

JP: Is this the same church, or is it a different church? What happened? And how did we get here? That adds a layer to the dystopian element.

CW: That, unfortunately, is a little underdeveloped in the final script version that I delivered. The whole revolution, for example. Who are the different people? You have the church against the city guard, for example. [There are] these different fractions. The overlord, you don't really know who that is, but he is basically held in power by the city guard, and then you have the church, which is a power player and is opposed to the city guard. I put that in because I felt it was related to Game of Thrones and the King’s Guard.

George mentions that a lot of [A Song of Ice and Fire] elements appeared in earlier stories. For example, the King's Guard is basically the same as the guards protecting the queen in In the Lost Lands. And Cersei has this conflict with the church in [the series too.] In Martin’s series, starting in book three, the church becomes a medieval fighting decadence type of group of people. I wanted to somehow refer to Game of Thrones a bit.

JP: One more question in reference to your other work. In your graphic novel One Night in Prague, you also have shapeshifting. What's your fascination with shapeshifting?

CW: That's because I like animals and I love in Game of Thrones when they go behind the wall, and there's a really interesting way that some of these characters or the wildlings relate to, for example, an eagle. Instead of turning into an eagle, they see through the eyes of the eagle; they can connect with the animal on a psychic level.

JP: In one of your other interviews, you mentioned the graphic novel series Monstrous as something that you'd like to be adapted at some point, and that also has an interesting relationship with animals and humans.

CW: That's also a very female-driven graphic novel.

JP: Yeah, that is true.

CW: I relate very much to women. It's difficult to put [into words]. It’s a mixture of reasons. My mother was the one who brought art and culture to me. I like that about Monstrous, and in general, there's a lot of female touches to what I'm doing.

JP: One more question about the ending. From my understanding, the ending in the short story was pretty different, and Martin didn't even know until he saw it about all the changes. I'm curious: what was the original ending of your screenplay?

CW: The same as in George’s.

JP: When did it change?

CW: That was Paul's decision. He felt that the ending was disappointing for people.

In the short story, the two characters are together for whatever, 10 minutes, and then one kills the other. It's a little different than if they are together for two hours and one kills the other. He knows his audiences, [still], I feel, to be perfectly honest, I probably would've killed the character at the end. He is very experienced with these kinds of things, and he's clearly directing films [knowing his] audience, whereas I think George and I are not so concerned about what the audience thinks or what the audience doesn't think.

You also have to think about the actors. You have Dave Bautista and Milla Jovovich. They are stars. So that was also always a consideration that we have to stay with stars and can't just discard them. Those are considerations that Paul is also really good at and really knows about.

JP: The structure is very circular, almost. That gives it a mythic feel. How did you play with the structure while you were writing?

CW: In this specific film, they’re cutting back to the city a lot, which is a little tricky in comparison to a classic adventure story. You might just follow these two characters and discover the fantasy world through the characters. What we have here is almost a bit like an episodic TV show. You have side stories, you have the story with the patriarch versus the Queen Melange (Amara Okereke). Then we have the people who are pursuing them. They're always kind of behind them.

Then we have Alice and Boyce themselves. To tie all of that together, Paul invented the beginning and the end. The very beginning, with the character telling the narrational stuff, that was not me. That was Paul’s edition. Otherwise, the film is structured actually after these nights, which I like because you have just so many nights until the full moon.

JP: It's like a ticking clock.

CW: Yes, a ticking clock. It's like a ticking clock. Night one, night two, night three, night four. I like all of that. It makes it a bit abstract, and then you have the map there and all this stuff. This was mostly added in post-production. These images of one night, two nights, three nights [came] later. He didn't have this in the script.

JP: That’s not surprising. His work has an obsession with maps as well as timekeeping and tracking the spatial and temporal relationship of characters. To me, the watch element felt like a natural extension to his fascination with physical geography.

CW: It's also interesting that he's obviously a master of choreographed fight scenes, and he uses either the clock or a time element all the time. I like when they have the first fight in the bar, and you have a spinning coin the entire time, simply because it gives a beat. When it hits the ground, the fight's over.

[It’s also there] in the scene with the werewolf against the eagle. He told me that when he did Alien vs. Predator, the fight at the end [with the CG characters] was never emotionally satisfying. That's why the scene at the end [of In the Lost Lands] is so super stylized. It's in the rain with thunder and lightning, and you have the clock flying through the air the entire time.

JP: It’s like his corrective to Alien vs. Predator.

CW: Yeah. [It’s hyper-stylized.] I like that.

JP: I have always found George R.R Martin to be this very, very American writer in the sense that the themes and concerns and anxieties of his work seem to resonate more strongly here than anywhere else. Here, you have a British director and a German writer adapting a very American author. Do you think of Martin this way? As a very American writer?

CW: I'm thinking of him as a European writer.

The [A Song of Ice and Fire series] is based on two things: the War of the Roses and the fall of the Roman Empire. He's a history major. He went to Northwestern University in Chicago and studied history. His fascination is clearly with Europe.

JP: You’re right about that.

CW: Stephen King, on the other hand, is a totally American writer. His books are about being bullied in high school. That's the bottom line of all of Stephen King's work.

JP: You don't get bullied in high school in Europe?

CW: No. And I’ll tell you why: because we don't eat at school. I went to school in Germany, and you come home for lunch, you go to school in the morning, you have your classes, and then you go home [or your] parents pick you up. You don't have so many interactions. This whole concept of the scary locker room doesn't exist because we don't even have any locker rooms.

Of course, you get bullied too. But I think that there are certain very typical American themes, and I don't see them in George’s work. The only thing that's very American is that, in his heart, he's actually a science fiction writer. And science fiction is the most American genre.

JP: Other than the Western, you might be right.

CW: I'm thinking in terms of the fantasy world. It's interesting that this fantasy it's so based on British stuff. [When we were with George and in interviews,] he said his favorite book is Watership Down… His two heroes are The Lord of the Rings and Watership Down. Those are very British. He's not referencing a classic American, for example.

I also would say that the witch, that's European witchcraft. It is not Salem.

JP: And of course, Milla is Ukrainian, to continue with the European feel of what’s on screen.

CW: She's the most witchy person ever. She is perfect for that.

JP: Just like her role in Hellboy. You look at it and you instantly recognize the genius of the casting.

JP: You've been working on this film for more than a decade. At any point, did you almost give up on trying to realize the project?

CW: Yes, in the beginning, in the very beginning. I optioned his rights right after The Pagan Queen [in 2009]. That was before Game of Thrones came out on HBO. Everybody knew it was going to come out because it was already filmed and announced and everything.

I was focused on the directing. As I said, I didn't really change the stories that much. And I worked with a producer in Hollywood who was supposed to put all the financing together and do the whole producing part. I didn't involve myself as a producer at all. I optioned the rights, and that was a producer part, but I did not do anything else. When that didn't work out, after two years, I gave up on it. [The rights expired.]

All of a sudden, Game of Thrones became such a big hit. Nico Bruinsma of Cult Epics convinced me to get the rights back. So, Nico and I went back to George and got the rights back.

That was really nice of George. I think I didn't have any rights at all for two years. We made a new contract, and everything was already different. His fame came with totally different lawyers and different companies it set up. In the beginning, it was very casual. The second time around, it was more, let's say, “high profile.” The contract was really long. And so, we went on the second journey.

As I said, unfortunately, I wasn't able to get the financing together. Then Paul came on board, and we would've done this years ago, but things got delayed several times. First, the movie Monster Hunter. We had to wait a year and a half until we could continue again. Once that was done, I was ready to go. And he met with me and shared that Milla was pregnant. That was great news, but it meant another year of delay. Then we got Dave Bautista, we got the film pre-sold, what happened next? Covid. That was another year and a half to two year delay.

JP: I don't want to take too much more of your time, so just two quick questions to end. Do you have ambitions to direct again?

CW: Of course.

JP: And then, what did you learn about directing from working with Paul WS Anderson on this film?

CW: What I learned from working with Paul is that I'm not going to even try to direct any action. It’s so complicated. It’s a difficult and challenging art form on its own. I was really amazed by how he did all of these action scenes. The work that goes into it: the stunt people were living there, this whole huge studio rented outside of Krakow. They spent months filming every single scene themselves. The stunt coordinators are unbelievable. I felt that to really look over somebody's shoulder while doing these complicated action scenes was an amazing experience.

I learned a lot about screenwriting because some of the things I told you are more with the thought about whether or not something works or doesn’t. That's not how I used to work at all. I was more like a novelist: I just write, and then hopefully other people like it too. But Paul really does not like dialogue. He is a visual storyteller. I have a theater background, and I like to work with actors on dialogue. But I definitely felt like everything from now on would have 50% less dialogue than if I had never met him. There is always so much exposition in everything I'm writing. Next time around, I will try to focus on the visual part.

JP: Thank you for this insight into In the Lost Lands, Constantin.

CW: Thank you so much.