Mission: Impossible – The Final Reckoning

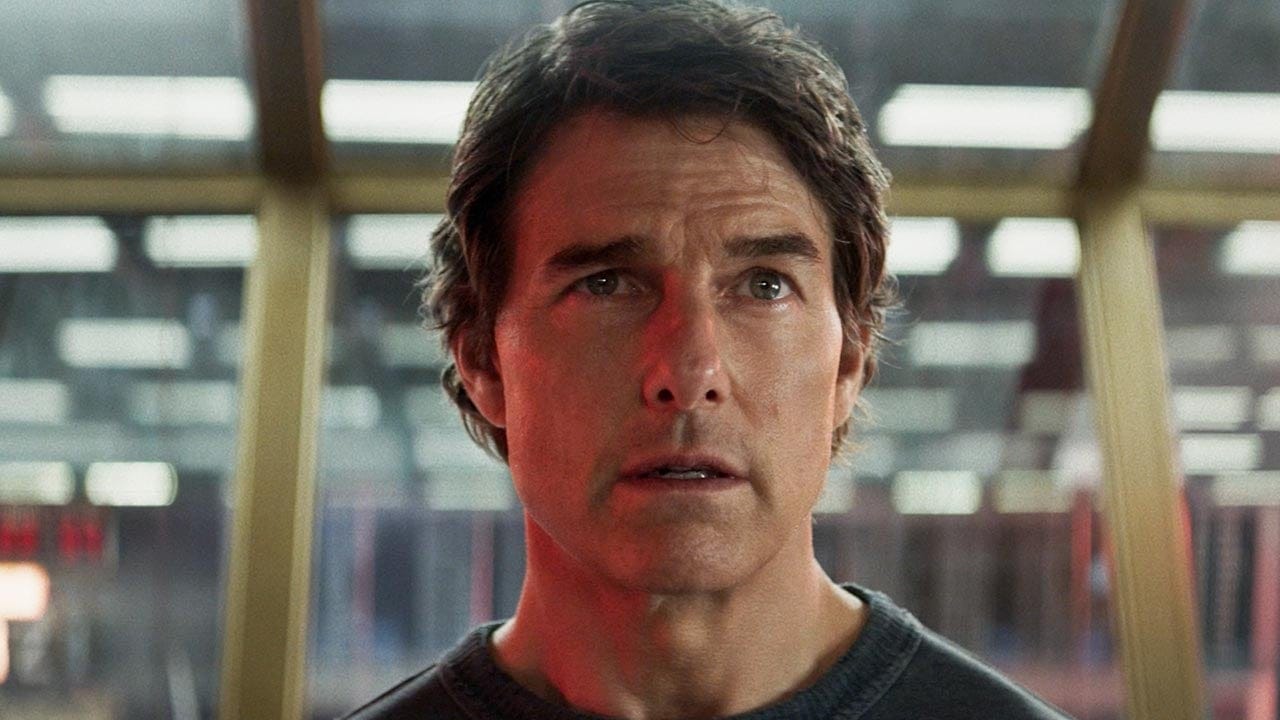

This is Tom Cruise at this best, at his most vulnerable, and at his most ambitious.

Every now and then a film comes around that temporarily revives my belief in Hollywood. Those films disproportionately star Tom Cruise, the last movie star and the savior of the multiplex. Cruise is alongside Jackie Chan as one of our greatest entertainers. If Mission: Impossible – The Final Reckoning is indeed the final film in Hollywood’s greatest spy series, we should count ourselves lucky to have had the opportunity to witness the whole saga in glorious IMAX. This is Tom Cruise at his best, at his most vulnerable, and at his most ambitious. This is “authentic” cinema, as he says in the brief theatrical introduction message.

In continuation of Dead Reckoning, the antagonizing threat of Final Reckoning is no nation-state or rogue agent but the Entity, a self-aware and omniscient global virtual virus of artificial intelligence that controls the world’s most important information networks and military assets. In Dead Reckoning, the AI showcased its ability to alter fact and challenge the basis for human knowledge — capturing fears so timely that the Entity scared President Joe Biden into ramping up protections against such possibilities. The Entity of Final Reckoning spends more time robbing the world’s global security strongholds of their nuclear weapons than interfering with the missions of Hunt and his team. Tom Cruise’s Ethan Hunt needs the cruciform key acquired in the previous entry to retrieve its source code from a sunken Russian submarine to destroy it — and he must kill the AI before it acquires the last of the world’s secure nuclear technologies and weaponizes them in a purge of human life.

Through the entire Mission: Impossible series, Ethan refuses to sacrifice the one to save the many. The many matter only because everyone else has their own Benji (Simon Pegg), Ilsa (Rebecca Ferguson), and Luther (Ving Rhames). Most of the time, he finds a way to save both the many and the few. When he doesn’t, the losses that tragically haunt him are always the faces of the few and not the indistinguishable crowds of the many: his team in Mission: Impossible, Lindsey Farris, Alan Hunley, Ilsa, the mystery woman Marie. Final Reckoning does what few finales do by challenging what comes before it. The apogee of the Ethan Hunt story reckons with the basic moral premise of the entire franchise: that the individual life matters as much as the lives of the many. Now he must choose the many over the few.

He could not save his great love of the series in Dead Reckoning. Ilsa died in a suicidal sacrifice to save Grace (Hayley Atwell), a world-class pick-pocket and Ethan’s strongest new bond. This time around, it is Luther, the last remaining friend from the first film, who discovers the undiscovered country. Luther, like Ilsa, gives himself up to save others: he can disarm the explosive of its full destructive potential, but he can’t escape. Ethan stands on the other side of a locked gate and must forsake his friend to save himself. Normally, he would never value his own life over a friend’s. This time around he has no other chance as only he can stop the Entity’s intention of nuclear holocaust.

The artificial intelligence “anti-God” and “Lord of Lies” challenges Ethan's moral prism more than any other villain has by complicating his anti-utilitarianism with monstrous efficiency and impossible (or deeply inhumane) choices. Consider how his ability to rely on his friends pauses for the first time in any serious way in Dead Reckoning in the Venice chase where Benji and Luther’s tech skills are made useless in the face of the omnipresent AI digital vacuum that is the Entity. Its machinery of anti-humanism is the perfect foil to Ethan’s superhumanism.

Four films in and Christopher McQuarrie’s direction has evolved enough to rebalance the story according to Ethan’s moral prism. As he is forced to forsake his friends to fate to save the rest of the world, for what is arguably a first for the entire franchise, his friends and their mission(s) share the main stage with him for the entirety of a film. The tasks of Benji and Luther, and to a lesser extent the others who tag in and out of Ethan’s team, have always been crucial to the IMF in limited sequences: Benji's pin-pointing of Julia’s location in MI3, the nuclear code swap in Ghost Protocol, the “second they will never get back” in Fallout. This is different. For almost the full run-time of the eighth film, Ethan is on his own, and his friends are on their own. The structure and editing divide and cut according to how Ethan sees others. I imagine others will not appreciate the degree to which this film removes itself from its main protagonist in the process of mythologizing him, but, for myself, the degree of separation is integral to the moral imagination of the finale where Benji, Luther, Paris, and Grace are made as important to Final Reckoning as they are to Ethan Hunt.

The submarine sequence may be the most thrilling and agonizing 20-plus minutes in the franchise. The underwater world encloses on Ethan as he dives to ungodly depths to recover the drive preserving the Entity’s source code. Water slooshes around and dislodges missiles; the shifting weight rolls the submarine unexpectedly even farther into the ocean’s depth, making his ascent more dangerous; the chill of the Arctic waters can kill; and with each passing second, the odds of him surfacing dissipate. Every threat alters his plan and adds another track to the chorus of ticking clocks.

He dies in the pristine blue water, shrinking into the fetal position of a biblical Adam. Grace’s kiss of life brings him to life in one of the most stylized shots of the film. At first, she appears underwater in her tank top kissing his freshly dead lips and the edit fades onto the ice surface where Grace and Tapeesa (Lucy Tulugarjuk), an Inuit woman, revive him. The romantic stylization of the kiss given through a baptism by submersion has little to do with their sexual chemistry and more to do with the beauty of life. Her lips gift him the grace he needs. They remind him of the life he has.

If he approaches the depths of hell in the ocean, he gets too close to heaven in the sky. Chasing Gabriel’s (Esai Morales) biplane with a biplane of his own in South Africa, the belly of his plane catches on fire and rapidly engulfs the vehicle. Falling from the sky like Icarus, Ethan jumps with an emergency parachute whose proper deployment comes only second to saving the world by connecting the submarine module to Luther’s poison pill as he falls. The genius of these two brushes with death is that one demythologizes Hunt through a reminder of his mortality, a reminder of his humanity, while the other scene revitalizes him as myth through Icarus, the Greek god who disregarded the warnings of his superiors and flew too close to the sun (and then drowned).

The “final” entry may be a masterpiece. It’s also messy. The penultimate submarine action set piece easily trumps the final airplane one and a little tinkering one way or the other could have rearranged things to end on the superior note. It's still a Mission: Impossible film, so by any metric, there are no complaints with the action. The critics who lament a lack of action need to unplug from the non-stop instant gratification of the internet just like Cruise’s protagonist tells a henchman that he beats to a pulp, “You're spending too much time on the internet!”

The slop may be the sloppiest in the uncompleted emotional threads left dangling. The seeds left in Dead Reckoning about Ethan’s past with Gabriel and the mystery woman Marie do not grow into something more well-nourished or well developed here. They both dissolve into the background. Theo Degas’s (Greg Tarzan Davis) character development stunts as he disgraces his loyalty to the US intelligence agencies and joins the once-again rogue IMF team. One also wonders whether the ultimate expression of the film’s ethical challenge would have meant even greater intimate loss for Ethan. Had either Benji or Ethan died, perhaps both, would The Final Reckoning be widely remembered as one of the most fulfilling blockbusters ever made? Maybe.

McQuarrie’s biggest misstep is that Benji never has the opportunity to mourn Luther, a man who has been glued to his side for the past several films. The mourning dirge likely got cut in the already ballooned run-time. Other than a tearful lip quiver by a brilliant Pegg at the mention of Luther’s name in a scene where Hunt mentions his “poison pill,” there is never an indication that Benji even knows his friend is dead.

Final Reckoning also doesn’t satisfy on its own. It also wasn’t meant to. Originally titled Dead Reckoning Part Two before being renamed, it's unsurprisingly fully dependent on the film before it. Ilsa’s death in the former meets the stakes of loss of Luther’s death in the latter and doubles the emotional impact of Ethan’s losses and grief. On its own, Luther’s death comes too early in the final entry to fully satisfy the requirement of great loss that the film demands; Ethan needs to lose greatly, whether that be himself or his friends, for the payoff to move beyond cathartic relief and toward sheer heroism.

Side characters and glorified extras from previous entries return as part of the messy bow that ties the series into one metanarrative about Ethan Hunt and his vocation to save the world. Most of each of the prior episodes stood independently from the next, but McQuarrie and co-writer Erik Jendresen reneged those missions into one-Endgamified climax. President Erika Sloane (Angela Bassett), the former director of the CIA in Fallout, asks for Ethan’s help in returning the key and all of his knowledge of what it unlocks to the United States’ government. Her message thanking him for his lifetime of service permits McQuarrie and editor Eddie Hamilton to cue up the series’ grandest self-indulgence: a montage of stunt highlights and greatest moments that plays like a long trailer for the eight MI movies. The montage delights in the immortal superman persona that Cruise reshaped himself into over the years and bites deep into the nostalgia of the franchise. The two scenes that transgress opposing verticalities— extremely low in the submarine and incredibly high with the plane — play with this self-awareness.

The stunts and sheer magnanimity of The Final Reckoning do not speak to a humble filmmaker. It is, however, the most spiritual film in the series. The mythological allusions play a big part in this, as does the easter-egg mythologizing of the Mission: Impossible series. (The release date of the first film, May 22, 1996, is a date that alters history through an unrelated event.) But so does everyday spirituality. Admiral Neely (Hannah Waddingham) passes on her St. Christopher medallion to Ethan, the villain is described in deified language, the key is cruciform, and their dependence on chance borders on providence. He even dies on behalf of all and is resurrected like Christ. Just like War for the Planet of the Apes, the religious dimension adds a biblical gravitas to the saga’s pinnacle.

More speculatively is the way Ethan Hunt’s past relates to the religiosity of Tom Cruise. One of the most fundamental practices in Scientology is auditing. The process looks something like a therapy session with an auditor asking questions and listening to the subject with the goal of helping them to remove or move past “charged incidents” stored in their subconscious through traumatic events. One could think of it as psychologically moving beyond one’s past. According to Scientology’s official website, auditing assists “the individual … in locating not only areas of spiritual upset or difficulty in his life, but in locating the source of the upset. By doing this, any person is able to free himself of unwanted barriers that inhibit, stop or blunt his natural abilities and increase these abilities so that he becomes brighter and more spiritually able.” Final Reckoning subverts auditing through its more grateful appreciation of the past. Rather than eliminating “neuroses” caused by the past, Ethan Hunt must evaluate his life’s work and embrace it. It is not about ignoring any harm he has caused to civilians or discharging harmful traumas of the past; instead, he must reckon with the past, and that is an entirely different process altogether.