Fritz on Fridays: Harakiri (1919)

One of the most underappreciated legacies of Fritz Lang’s career was his star-making power.

On the first Friday of every month, this column by critic Joshua Polanski will feature a short review or essay on a film directed by Fritz Lang (1890-1976), the great Austrian “Master of Darkness.” Occasionally (but not too occasionally), Fritz on Fridays will also feature interviews and conversations with relevant critics, scholars and filmmakers about Lang’s influence and filmography.

One of the most underappreciated legacies of Fritz Lang’s career was his star-making power. He made movie stars just as much as he worked with pre-existing ones. It’s one of the major lines of continuity in his multi-decade and multi-continental career.

Two of the most important stars Lang burned into celluloid history were Lil Dagover and Friedrich Rudolf Klein-Rogge. Dagover would star in five of Lang’s silent-era films: Harakiri, the two Spiders films, Destiny and Dr. Mabuse, the Gambler. Five may not seem like a lot, but there are very few actors Lang worked with as often as Dagover; possibly only Klein-Rogge, whom Lang would work with in his early sound years, surpasses Dagover’s number of appearances in his filmography. What both actors have in common is that their early career collaborations with Lang propelled them to the top of the German and European film industries. Klein-Rogge was little more than an uncredited extra until The Wandering Image, and Dagover would summit the Weimar industry in films by F. W. Murnau, Michael Curtiz and Lang after making it big with 1919’s Harakiri.

The second-earliest not-lost film of Lang’s expansive career, Harakiri adapts Giacomo Puccini’s opera Madama Butterfly, a title the film was also known as in its original release in the United States because of the existing familiarity with the source material. The film was considered lost after the war and through most of the 1980s and, as a result, is rarely mentioned in larger contextualizations of Lang’s filmography. Tom Gunning’s 540-page book on the director, The Films of Fritz Lang: Allegories of Vision and Modernity, mentions the title a meager two times. In 1987, a Dutch print was rediscovered in a vault and subsequently restored and re-released, although that did little to help its status.

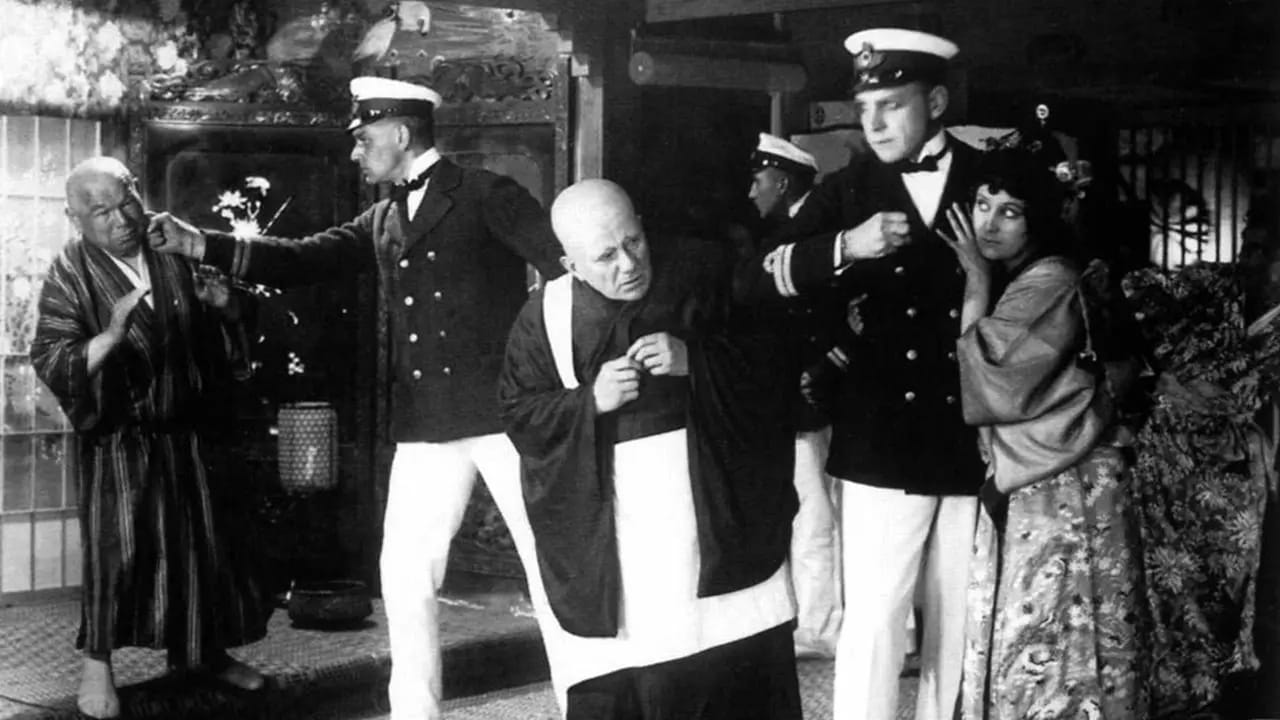

Dagover plays O-Take-san, the daughter of Daimyō Tokujawa (Paul Biensfeldt, himself appearing in four Lang films). The daimyō is returning to Japan from an ambassadorship in Europe at the turn of the 20th century. A Buddhist monk wants O-Take-san to become a priestess and ends up framing the daimyō for treason and treachery, prompting the Emperor to send a sword to the family home to demand he show loyalty by committing harakiri, or seppuku). In line with Lang’s usual themes of control and freedom, O-Take-san falls under the pinching control of the monk, and the path of escape she chooses is based on some culturally determined marriage of 999 days (exactly). A season of lies and love affairs later, O-Take-san follows in the footsteps of her father and kills herself with the (Freudian) sword the emperor once gave to her father.

Continue reading at the Midwest Film Journal.